Planarian flatworms are small, flat-bodied freshwater invertebrates known for their remarkable regenerative abilities. With a distinctive elongated body shape covered in cilia, these animals range in size from just a few millimeters to several centimeters in length. They have a simple nervous system, primitive “eyespots,” and a single opening that serves as both a mouth and an anus.

A while back, scientists have made a remarkable discovery regarding planarian flatworms. In an experiment involving the decapitation of trained worms, biologists found that these regenerative creatures were capable of retaining memories and transferring them to their newly regrown brains.

The research was led by Michael Levin, a professor at Tufts University, and Tal Shomrat, a former colleague. Their findings, which were published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, suggest that the study of planarians could offer insights into how memory might be stored in tissue and potentially retrieved, which could prove valuable as regenerative medicine advances to a stage where human brain tissue can be replaced or replenished with stem cells.

Planarians, known for their ability to regenerate any part of their body, are non-parasitic flatworms with adult pluripotent stem cells that have the potential to become any cell in the body. This makes them an excellent model for regeneration studies, as they are continually growing and shrinking. In fact, a study from 1898 showed that a planarian could rebuild itself from a tiny fragment just 1/279th the size of its original body.

Despite their fascinating regenerative capabilities, studying the cognitive abilities of such a basic invertebrate has proved challenging. However, Levin and Shomrat overcame this by using video-tracking technology to build a scenario where planarians could be trained to go into the light for food.

Two groups of flatworms were placed in different environments, one with a ridged surface and one with a smooth surface, and their behavior was tracked to measure their aversion to bright light. The worms on the rough surface appeared to overcome their fear of light much faster than those on the smooth surface.

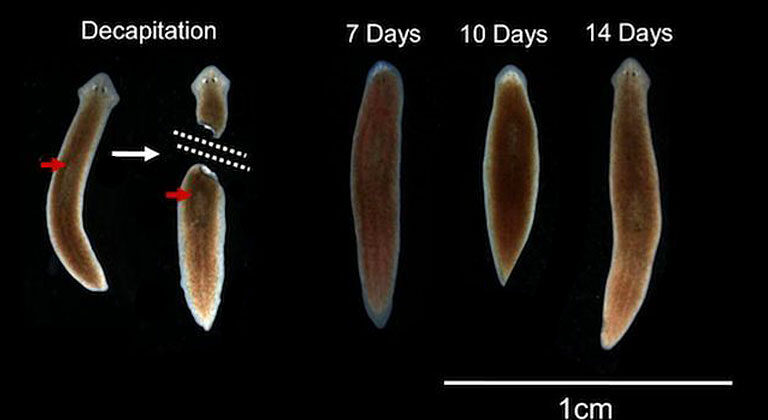

To further explore this, Levin and Shomrat decapitated the worms and tested them for an aversion to light once their heads had regrown. They found that the trained flatworms were slightly quicker than the untrained worms in adapting to light. The researchers believe that planarians could be a valuable model species for investigating how specific memories are encoded in biological tissues and that their findings could have important implications for stem cell-derived treatments for degenerative brain disorders in humans.

While the scientists are not yet certain how or where the flatworms are storing their memories, they believe that this research offers a promising starting point for further investigation.